Introduction

WordPress can be an effective, economical and efficient way to manage your higher education institution’s digital presence and can be used to promote your organization’s goals.

To be clear, higher education is a phrase that refers to many institutions: two-year community colleges, vocational schools, four-year universities, graduate schools, seminaries, public and private non-profit, for-profit institutions and many other diverse organizations. Each institution faces its own challenges and handles their digital presence differently.

No matter the name, the underlying goal of each institution remains the same: to educate students. Each institution uses its digital presence to distinguish itself from other institutions.

While WordPress will not be the choice for all higher education institutions, it may be the right choice for yours. It’s currently used in myriad different situations in higher education, from a simple blogging platform to a full-featured content management system (CMS) and everything in between.

Benefits of WordPress for Higher Ed

WordPress is extremely inexpensive when compared to many other platforms. It offers flexibility, control over the division of responsibilities and includes greater support than any other platform.

Cost

By itself, WordPress is as inexpensive as a platform can be; it’s free. In addition, it’s open-source and runs on free, open-source platforms. The standard operating system used to host WordPress is Linux. Apache is the standard Web server on which WordPress runs, but it can be set up to run on nginx, Varnish and Microsoft IIS (the only server that is not free and open-source) and it only requires PHP and MySQL to function.

The only costs required to set up WordPress are the costs associated with hardware, bandwidth and network resources; costs associated with any platform.

However, that doesn’t mean it’s free to create and maintain a WordPress system. To use WordPress effectively, you may consider premium (purchased) WordPress plugins and themes, which can greatly increase the efficiency of creating, developing and maintaining your custom design. While the total cost of these purchases could be a few thousand dollars each year, the cost is minimal compared to the cost of large proprietary systems on the market.

Openness

Another benefit of WordPress is that it’s open-source. Since WordPress is written and documented extremely well, it’s simple to modify WordPress to fit your institution’s needs.

In addition, the ability to use and contribute back to a project as open and democratic as WordPress is an excellent way to demonstrate your institution’s fundamental goals.

Flexibility

WordPress is extensible and incredibly flexible. It can be modified to do just about anything that’s possible on the Web. Through the robust theme and plugin application programming interface (API), many modifications are possible without ever touching the core code.

This flexibility is part of what allows WordPress to be used in so many different situations. It can be used to create standard blogs, photoblogs, ePortfolios, microsites, student portals, employee directories, campus maps and virtual tours, learning management systems, presentations and lectures, open courses, social networks and full-featured websites, among many other uses.

As of August 2013, there are over 25,000 public, free plugins available in the WordPress plugin repository. Plugins extend the functionality of WordPress, adding custom functions and features such as spam filters, contact forms, photo galleries and more. New plugins are created and released every day. Many of the plugins were developed by and for higher education institutions.

Distributed Responsibilities

Along with its flexibility and openness, WordPress offers easy-to-use tools to manage the distribution of responsibilities. You can create users with full administrative permission, with the ability to add and edit new files, create new websites and projects, manage user accounts, perform system updates and more. Or you can create users who only have permission to view the content of the site. You can also create users with any combination of the capabilities in between.

Out of the box, WordPress has five user roles with different abilities and permissions :

- Subscriber – view private content, manage their own profile and potentially comment on the site without moderation

- Contributor – create new posts, but cannot publish any content or edit any published content

- Author – create and publish new posts, but cannot edit anyone else’s content

- Editor – create and publish new posts and pages, and to edit other users’ content

- Administrator – manage the entire site; including installing and activating new plugins and themes, managing menus and widgets, managing all content, performing system updates and managing users

Each role consists of different, individual capabilities. Each of those capabilities can be assigned to specific users, and new roles can be created easily.

In WordPress Multisite, the administrator loses the ability to install new plugins, and a new user role of Network Admin is added that has the capability to create new sites and install new plugins and themes.

Market Share and Support

According to BuiltWith, WordPress is used on nearly 51% of the top million sites on the Web; nearly three times as much as Joomla and Drupal combined. According to W3Tech, WordPress is used on more than 58% of websites that use a CMS; it is used on nearly 19% of the Web overall (including sites that are not using a CMS).

Based on those statistics, WordPress has an enormous user base; the self-hosted version of WordPress 3.5 was downloaded more than 27 million times between its release in December 2012 and July 2013. Over 68 million blogs and sites are currently running on WordPress.com.

WordPress has more users than any other CMS; in fact, it has more users than all of the other content management systems combined. It is used on nearly six times as many sites as the next closest CMS monitored by W3Tech. As a result of its huge user base, and the open community fostered by the WordPress Foundation and Automattic (the company behind WordPress), it has greater support than any other system in use.

While the official support community is free, and primarily managed by volunteers, Automattic pays multiple employees to manage the support forums, as do many Web hosts and consulting agencies.

There is rarely a question about WordPress that can’t be answered by visiting the support forums, checking the WordPress documentation, reading WordPress-related blogs and websites or looking through the source code.

The overwhelming majority of support questions on WordPress can be answered in a few minutes through a little research, without the need to pay for premium support. The official WordPress documentation is more robust than many other systems. Since the documentation is maintained on a wiki, anyone can contribute and expand.

Breaking Down Myths

While exploring WordPress for the University of Mary Washington (UMW), I encountered several concerns and myths, including that WordPress was:

- Simply a blogging platform, incapable of functioning as a full-featured CMS

- Difficult to customize; all WordPress sites look the same

- Full of security exploits and the safety of sensitive information

- Unable to scale or perform well on large sites

- Slow

After careful examination, I concluded none of these concerns were valid.

Myth 1: WordPress is Just For Blogging

Though WordPress began as a blogging platform, it has evolved into a more robust system. Saying that WordPress is just for blogging is akin to saying that cell phones are just for phone calls. That’s far from the only use case for WordPress, and blogging is definitely not all it’s capable of doing.

With the release of WordPress 3.0, which introduced custom content types and implemented multisite functionality into the core, WordPress evolved quickly into a full-featured CMS, application platform and more.

At UMW, we use WordPress as a:

- CMS for the entire university website

- turn-key solution for microsites and landing pages,

- ePortfolio system

- photo gallery

- blogging platform

- system for open-courses and a platform for applications like employee directories and campus maps.

Other colleges and universities are also using WordPress to implement student portals, social networks, learning management systems and countless other solutions.

Myth 2: WordPress is Difficult To Customize; All WordPress Sites Look The Same

WordPress is extremely simple to customize; it requires knowledge of PHP, HTML and CSS, but little more. The entire system is extremely well-documented; you can easily research the various APIs built into WordPress.

The Theme API in WordPress is a straightforward and simple-to-use theme system. You write the HTML and CSS you want to use on your site and plug in the standard PHP variables and function calls where they need to go. The Plugin API is also very simple. And the large number of hooks within WordPress make customization of its appearance and functionality extremely easy.

Within higher education, it’s usually “all higher education sites look the same” rather than “all WordPress sites look the same.” A WordPress site can be customized to look and act the way you want. It can integrate seamlessly within an existing solution. If it can be done with HTML, CSS and JavaScript, it can be done in WordPress.

Myth 3: WordPress Is Full of Security Exploits

The key to keeping WordPress secure is to ensure the system is well-maintained and kept up-to-date. Any potential security exploits can be kept at a minimum with a minimum of preventive work. The WordPress core itself is extremely secure, but you need to be vigilant about any other code used on your site, and the behavior of your website managers.

There are few security holes in WordPress core. An article on WPMU.org from 2012 explains parsing the different types of security issues related to WordPress and what types of issues you’ll find in the WordPress core. As of July 2013, if you search the National Vulnerability Database for security issues in WordPress 3.5.2, you will only find nine results, eight are related to “WordPress before 3.5.2” (meaning that they were most likely fixed in 3.5.2).

However, a vulnerability in a third-party plugin or a vulnerability in an external library still results in a vulnerability on your site. While the source of the exploit may not be WordPress itself, your website may be vulnerable. If you keep WordPress up-to-date, and take a few basic precautions, WordPress can be extremely secure, assuming the platform on which you have it running is also secure.

Myth 4: WordPress Doesn’t Scale

WordPress scales extremely well, given the system is well-maintained and the server is configured appropriately for WordPress. WordPress.com hosts over 68 million blogs and sites on a single, custom instance of WordPress. According to the WP.com stats page, nearly 10.7 billion pages were viewed in June 2013 (including self-hosted sites using the JetPack Site Stats module).

At our school, UMWBlogs supports over 7,000 blogs and sites, with nearly 10,000 user accounts, on a single instance of WordPress Multisite. As of July 2013, the UMW website has 294 sites spread out across 51 multisite networks, nearly 10,000 posts and almost 15,000 pages in a single instance of WordPress. There are more than 2,000 registered users in the system.

Myth 5: WordPress Is Slow

At times, WordPress can be slow. However the issue is not usually WordPress performance. Rather it’s the performance of the Web server, firewall, or database management system that isn’t keeping up with the number of requests being made.

It’s not difficult to keep WordPress running efficiently, as long as the system on which it’s running is configured properly. In many cases, a caching plugin will do everything to assure a WordPress site loads and responds quickly. In other cases, it may be necessary to use a cache server and possibly even a load-balancer to make the system run more efficiently.

Testing WordPress Scalability and Speed

To demonstrate WordPress’ scalability and speed, I ran load tests using blitz.io on five slightly different configurations.

Test 1: W3 Total Cache, Dropbox and Photon on Shared Hosting

I ran a test on a graphics-heavy site running on a single shared hosting plan that uses the Photon module within JetPack to load images off of WordPress.com’s content delivery network (CDN). The total size of the home page is 1 megabyte, and there are a total of 115 separate HTTP requests on the page. The site includes widgets that load content from Twitter, Facebook, Dropbox, WordPress.com and a handful of other external services. During that test, the first timeout (longer than 1 second loading time) occurred after there were 63 concurrent users on the page. Until the test reached more than 50 concurrent users, the load time was under 300 milliseconds. After that point, however, the site only responded successfully a handful of times throughout the rest of the test. In this case, this site usually uses CloudFlare Content Delivery Network (CDN) to balance the load and manage the cache, but that had to be disabled in order to run the test.

Test 2: W3 Total Cache and Photon on Shared Hosting

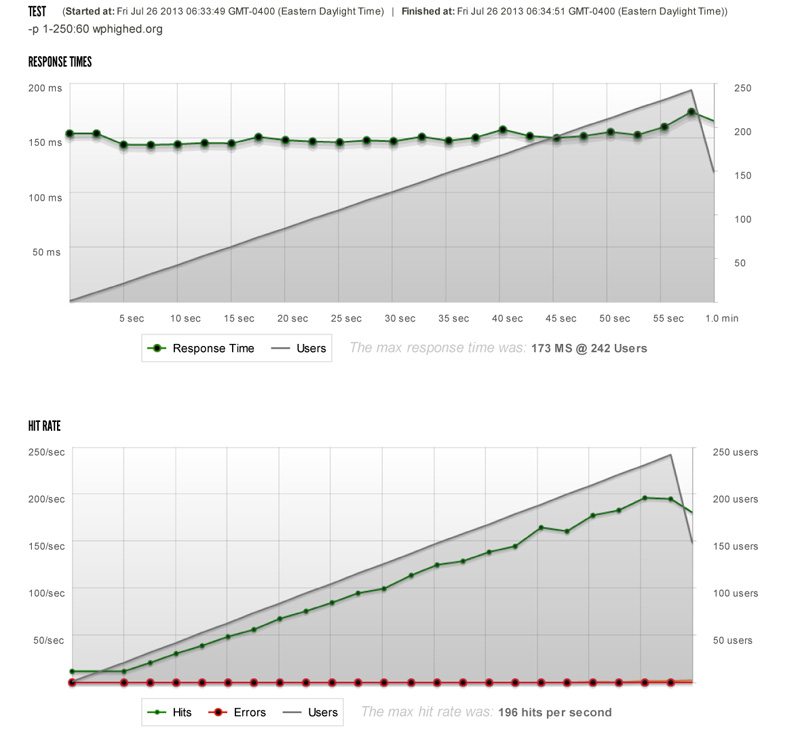

The second test I ran was on WPHighEd, currently hosted on the same type of hosting account, from the same hosting provider as the site in Test 1. This site is running W3 Total Cache and Photon, as well. The home page of the site makes a total of 58 HTTP requests, and weighs in at 1.2 megabytes. A total of 21 of those HTTP requests are made against external servers; most of those being images that are loaded from WordPress.com’s CDN. During this test, the first timeout occurred after there were 73 concurrent users on the site. Shortly after that, much like in the first test, the site began timing out for all requests. Until that point, though, the site averaged a 180 millisecond response time. This site also generally uses CloudFlare as a proxy cache, but that had to be disabled for testing purposes.

Test 3: WPEngine Hosting

I moved WPHighEd to WPEngine and tested it again after the move was completed. The site is still configured to use Photon, but no longer uses W3 Total Cache; instead, it uses WPEngine’s built-in caching system. At this point, with one or two additional plugins disabled and removed, the home page was still 1.2 megabytes, but only ran 54 HTTP requests. There were 6,392 separate requests, and only 17 resulted in a timeout. The first timeout occurred when there were 210 concurrent users on the site. The average load time was 175 milliseconds.

Test 4: W3 Total Cache on Shared Hosting

I ran a separate test on a test installation of WordPress with nothing but a slideshow on the home page. This site is running on a separate shared hosting account, hosted by a different provider than the first. The total size of the page request is 1.5 megabytes, and there are 32 separate HTTP requests. The HTTP requests come from 3 different sources; the site itself, the UMW web server and a single request from the Google Fonts server. This site is also configured to use W3 Total Cache. In this test, a total of 4,812 separate requests were made on the server; only 7 of those resulted in a timeout. The first timeout occurred when there were 179 concurrent users on the site. The average load time was 465 milliseconds. This is a development and test site, so it does not use any type of proxy cache on a regular basis.

Test 5: Nginx Proxy Cache on Dedicated Server

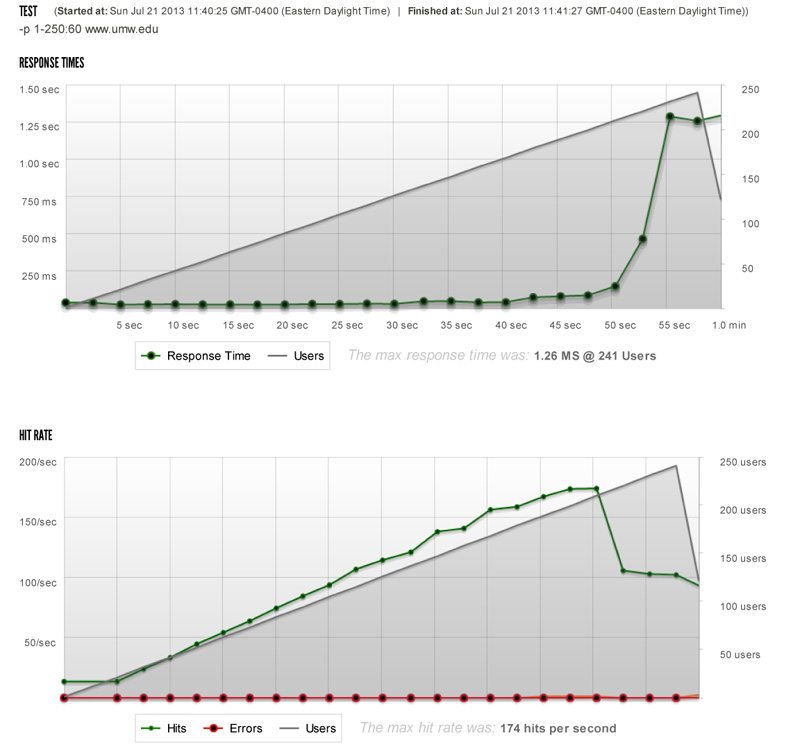

I also ran a load test on the UMW production website itself. The UMW website is served from a cache by an nginx proxy server and uses no other caching. The total size of the home page request was 1.8 megabytes with a total of 109 separate HTTP requests. There are approximately 5 calls to Google’s Analytics CDN for various pieces of that script, a call to WordPress.com for the JetPack Site Stats tracking pixel, and a call to Twitter for its widget script. Other than that, the rest of the HTTP requests are made against the UMW server. In this test, a total of 5,896 separate requests were made on the server; only 9 resulted in a timeout. The average load time was 260 milliseconds.

Test Results

|

# |

Host Configuration |

Caching |

HTTP Requests |

Size of Page |

# of Successful Hits |

First timeout |

Avg. Load Time |

|

1 |

Shared hosting |

W3 Total Cache, Photon for images, |

115 |

1 mb |

350 |

63 concurrent users |

125ms |

|

2 |

Shared hosting |

W3 Total Cache, Photon for images |

58 |

1.2 mb |

741 |

73 concurrent users |

169ms |

|

3 |

WP Engine |

WP Engine caching, Photon for images |

54 |

1.2 mb |

6,392 |

210 concurrent users |

151ms |

|

4 |

Shared hosting |

W3 Total Cache |

32 |

1.5 mb |

4,812 |

179 concurrent users |

465ms |

|

5 |

Dedicated server |

nginx proxy caching server |

109 |

1.8 mb |

5,896 |

189 concurrent users |

260ms |

Based on these tests, it becomes clear that the performance and reliability of WordPress relies as much, if not more, on the configuration of the server than it does on the WordPress system itself.

The two tests running on the same type of shared hosting account were able to keep up for a while, responded relatively quickly up to a certain point, but bottomed out after a certain number of requests. In the third test, I ran the test on the same WordPress site that was tested in the second test, but on a different host, with very different results. In the fourth test, the site responded a bit more slowly, but it was able to keep up throughout the entire test. In the final test, the site responded fairly quickly and kept up fairly well throughout the entire test.

In all test cases, the sites are running on the latest version of WordPress. Even though the fifth test was the largest page with the second-highest number of HTTP requests, it performed the best.

It should also be noted that, in similar tests in the past, the account tested in the fourth test was used as a clone of the UMW website, using W3 Total Cache instead of the nginx proxy cache that’s present on the production UMW server, and responded very similarly.

One More Test

As a final test, I decided to test the response time of a handful of different sites by performing a single blitz.io request; some of the sites are running WordPress and some are not.

|

Site Name |

URL |

WP? |

Size of Page |

HTTP Requests |

Response Time |

|

University of Mary Washington (UMW) |

http://www.umw.edu/ |

Yes |

1.8 mb |

109 |

57 ms |

|

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) |

http://web.mit.edu/ |

No |

228 kb |

16 |

51 ms |

|

University of Arkansas Little Rock (UALR) |

|

Yes |

906 kb |

54 |

267 ms |

|

College of William and Mary |

http://www.wm.edu/ |

No |

2.7 mb |

73 |

228 ms |

|

University of Southern California (USC) |

http://www.usc.edu |

No |

2.3 mb |

46 |

342 ms |

|

WP Engine (non higher ed) |

|

Yes |

794 kb |

118 |

93 ms |

WordPress at the University of Mary Washington

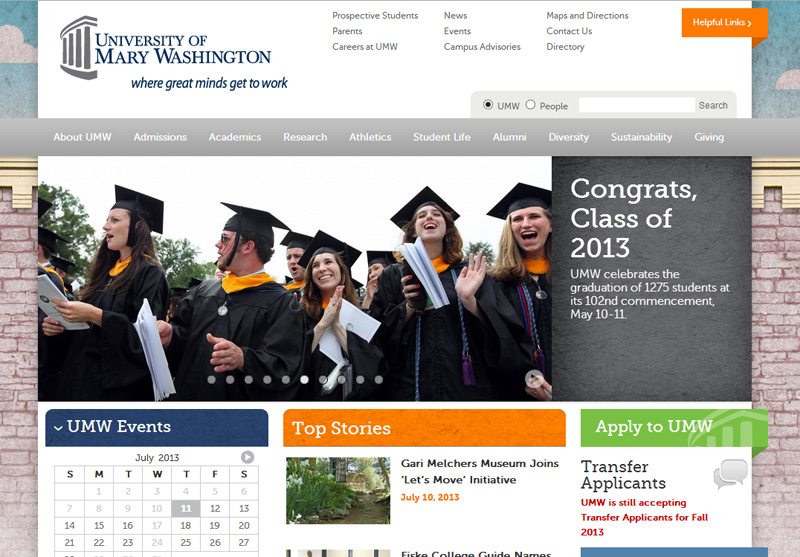

At UMW, how WordPress is being used has changed over the years. In July 2007, UMWBlogs was created using WordPress MU, to provide all faculty, staff and students at the university the ability to create their own blogs and websites easily. In the first six months, over 600 new blogs were created.

The open, collaborative, trusting community within the University relished the opportunity to build new blogs and sites quickly, and began churning out great content quickly. The users adapted very easily to the WordPress interface. In 2010, when UMW began to consider content management systems, nearly 4,000 separate sites had been set up within UMWBlogs and over 5,000 users were using the system.

When I was hired in late 2010 to begin developing the new WordPress system to manage the University website, we implemented WordPress as a multi-network environment, meaning that we are running multiple Multisite networks in a single installation of WordPress.

In order to begin using WordPress as a CMS, we had to identify which plugins would work with our system and modify those that didn’t work the way we wanted. As part of that process, I branched an Active Directory (AD) authentication plugin to work in our environment, allowing all of our users to login using their AD username and password. I developed a new plugin to generate our employee directory from AD data and created extensions for a handful of plugins to make them work more effectively in the multi-network system.

At UMW, we use nginx as a proxy cache in front of the Apache Web server that’s running WordPress. Through basic load-testing, we found that the site performed just as well using W3 Total Cache as it did using the nginx proxy cache. The difference was that nginx was configured to be able to handle more requests at a single time than Apache, so the website continued performing during higher traffic situations with nginx in front of Apache.

With two or three exceptions, we use a single custom Genesis child theme throughout the UMW website. We have 99 plugins installed and 36 various MU-plugins in place.

Over the past year, the website has had over two million unique visitors; UMWBlogs has had over 1.7 million. During that time period, the website averaged a total of approximately 463,000 visits and over 1.5 million page views per month. UMWBlogs averaged over 190,000 visits and nearly 366,000 page views per month.

In spring 2013, the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies (DTLT), the same group that initiated and manages UMWBlogs, launched a pilot project called “A Domain of One’s Own”, offering a free domain name and free hosting space to incoming freshmen to facilitate the management of their online identities. UMW students were free to install and configure any Web-based software they desired; many of them installed WordPress.

Many of the sites are being used as ePortfolio systems for the students, showcasing the work they’re doing in class and outlining their experiences at UMW and beyond. The project was such a success, it was expanded to all incoming freshmen for the fall 2013 semester. The DTLT office implemented an application to identify when a new WordPress site is installed throughout the project, and automatically syndicates it to a central location.

Throughout UMW, WordPress is used in many different ways. The list of faculty members is a combination of data pulled from the Banner course list, the AD list of employees and custom user metadata within WordPress profiles. The magazine is implemented as a network of sites, with a new site created for each issue. The internal newsletter “EagleEye” is a WordPress site that allows story submissions from the greater community, and the student newspaper “The Bullett” also runs on WordPress.

In addition, the UMW map is implemented as a custom mashup between Google Maps and WordPress custom posts. Within the UMWBlogs system, some courses use WordPress to present academic assignments and projects. There is even a site that acts as the home to the huge, multi-institution open course DS106.

No matter the use, everyone within the UMW community embraces WordPress and takes it to new levels.

Adoption of WordPress in Higher Ed

UMW is just one of many higher education institutions using WordPress. Many institutions are using WordPress as the main CMS at the institution, including Allegheny College, Washtenaw Community College, University of Central Arkansas, Maryville University, Lafayette College, Southern Arkansas University at Magnolia, the University of Rhode Island, Erikson Institute, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Blue Ridge Community and Technical College, Georgia State University, John Carroll University, the University of Maine, Nicholls State University and many more.

Others, such as the University of Virginia, Boise State University and the University of Florida are using WordPress to present the top-level site, and many of the departmental and division sites. While the University of Michigan, Florida International University, the University of Missouri, the University of Rochester, West Virginia University, Concordia University and Penn State University are using other solutions to present top-level sites, they use WordPress to implement various departmental and division-level sites.

Quite a few schools also use WordPress to present news and magazine sites. Vanderbilt University, Carleton University, Berea College, Boston University and St. Louis Community College, among others, are using WordPress as a centralized news system, while schools like Missouri S&T are using WordPress to present the online version of their alumni magazines. Likewise, schools like Elizabethtown College and American University’s Washington College of Law are using WordPress to manage the online versions of their student newspapers.

WordPress is also used regularly to create microsites and landing sites within larger organizations. The student government organization at California State University Sacramento (Sacramento State) runs its site on WordPress, Portland Community College used WordPress to create not only its central news repository, but also a landing site to celebrate the college’s 50th anniversary. The Milwaukee School of Engineering uses WordPress to present its Admissions site.

In addition, WordPress is used as a social network, or online “Commons”, at many schools. CUNY Academic Commons is a central social network for faculty, staff and graduate students within the City University of New York system. Tufts University uses WordPress as a central blogging and conversation system in its Roundtable Commons.

Of course, many schools are using WordPress as a traditional blogging system. Carleton University, the University of British Columbia, the University of Melbourne, Longwood University, Boston University, Missouri State, University of Texas Austin, Harvard University Law School, the University of Washington, Princeton University, Cornell University and countless others offer blogs to students, staff and faculty throughout their communities, while schools like William & Mary and Saint Louis University use WordPress to host many of their featured student blogs.

Hundreds of WordPress plugins have been created and released by higher education institutions and employees within higher education. University of Mary Washington, Boston University, the University of Lincoln, Maryville University, University of Texas Dallas, Texas A&M and Duke University are among the many schools that have released public WordPress plugins.

Many schools also contribute to the WordPress core, while institutions like CUNY are heavily involved in the development of systems like BuddyPress, which offers social networking features. In addition, developers and authors such as Stephanie Leary, Chris Wiegman and Boone Gorges all worked in higher education when they began developing for WordPress.

Conclusion

The open, collaborative, inclusive community surrounding WordPress is a perfect fit for the mission of higher education institutions. We are all able to benefit from the lessons learned and the ideas and projects created by others; we can also share our ideas and projects with the world.

While the WordPress community encourages that type of sharing throughout the world, the system itself encourages incredible innovation. WordPress is extremely flexible, incredibly cost-efficient, simple to use and better supported than any other system in the world. While WordPress is certainly not appropriate for every application, it is perfect for an amazing number of situations within higher education.

Click to view table

Click to view table Click to view table

Click to view table

Start the conversation.